Contact person

Specialised oncology consultation:

Registration for the special consultation under Info for doctors

Therapy and research in the Department of Internal Medicine III

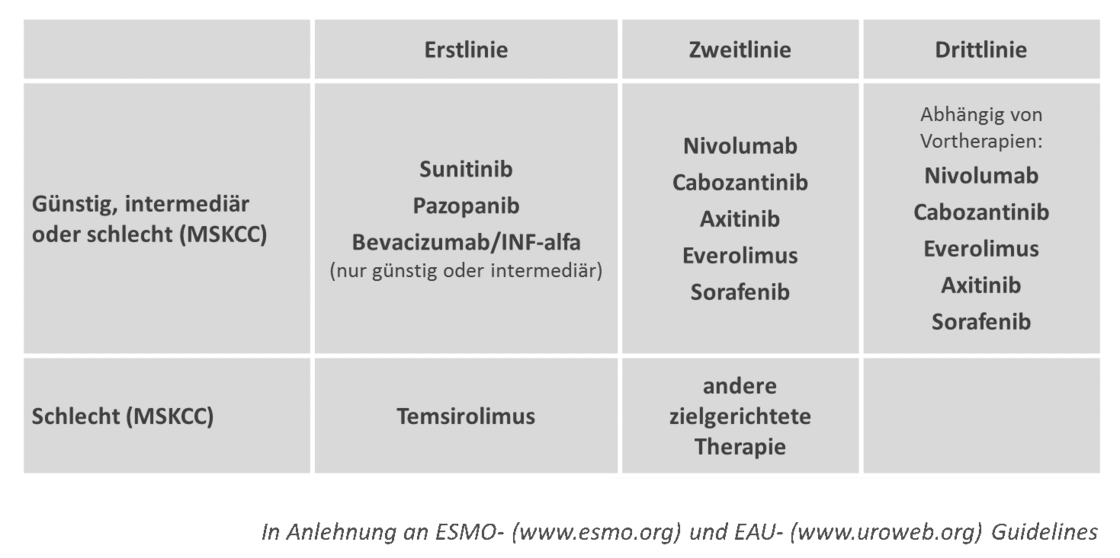

The treatment of metastasised renal cell carcinoma has changed fundamentally over the last 10 years. Whereas until 2005 systemic therapy was limited to immunomodulation using the cytokines interferon-alfa and interleukin-2, in recent years molecularly targeted strategies such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies have become important in the treatment of metastasised inoperable renal cell carcinoma. Immunotherapy has also made significant progress. The so-called checkpoint inhibitors have not only shown clear efficacy in clinical trials, but also that tumour growth can be contained in the long term in some cases. However, due to the lack of clinically applicable predictive markers, it is currently not possible to select those patients who will preferentially benefit from one of these therapies. The guidelines of most specialist societies provide for a risk-stratified therapy approach in which patients are categorised into risk groups using the MSKCC score. The resulting therapy recommendation is limited to the new substances in first-line therapy in all risk groups. In the majority of cases, several substances with different efficacy profiles will be used as sequential therapy during the course of the disease. The optimal sequence is currently still being investigated in clinical trials.

An inactivated VHL protein leads to reduced degradation of the transcription factor HIF-alfa in clear cell renal cell carcinomas. This results in increased production of substances such as VEGF and PDGF, which are essential for vascular growth within the tumour. An alternative activation mode of the tumour cell is the pathway via PI3-K, AKT-PKB and mTOR. The pathways are linked, as mTOR regulates the translation of HIF-alfa. The sites of action of all substances mentioned in the text are indicated in the tumour cell and the endothelial cell.

All stages and forms of renal cell carcinoma are treated at Ulm University Hospital. The Department of Internal Medicine III specialises in the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma and in conducting controlled clinical trials. The aim of these clinical trials is to improve current standard therapies and to research individual risk factors.

Clinical studies

Further information on the active studies can be found at:

Description of the disease

Renal cell carcinoma is a malignant disease of the kidney.

Frequency and age of onset, localisation

Malignant kidney tumours account for around 3% of all malignant neoplasms in adults. In Germany, around 5700 women and 8300 men are newly diagnosed with kidney cancer every year. The average age of onset is 63 years for men and 67 years for women. Men are about 1.5 times more likely to develop the disease than women.

Malignant tumours in the kidney are named after the tissue from which the tumour has developed. Around 90% of all kidney tumours are renal cell carcinomas. The remaining 10% are sarcomas, nephroblastomas (Wilms tumour), embryonal carcinomas or neuroblastomas.

The rather rare renal pelvis carcinomas arise from the mucous membrane of the urinary tract and are therefore not renal carcinomas, but belong to the bladder or ureteral carcinomas and are treated differently accordingly.

In most cases, only one kidney is affected by the tumour. In only about 1.5% of cases are both kidneys affected.

Signs of illness

Kidney carcinomas rarely cause symptoms in the early stages and are therefore often discovered by chance, e.g. during an ultrasound examination. Pain in the flank or back, blood in the urine (reddish to brown discolouration) can be an indication of kidney disease, as can colic, weight loss, anaemia, fever, high or low blood pressure, intestinal problems or constant fatigue. However, these symptoms often have harmless causes.

Early detection offers the best chance of a cure for malignant tumours.

Classification and staging

In order to determine the most suitable therapy, the above-mentioned diagnostics must be used to determine exactly how far the tumour has spread before therapy begins, i.e. the tumour stage is determined. The TNM classification is used for this purpose (see table below).

T stands for the size and extent of the primary tumour, N stands for the number of affected regional lymph nodes and M stands for the occurrence and localisation of distant metastases (tumour metastases).

TNM for renal cell carcinoma according to UICC 2002

TX Primary tumour cannot be assessed NX Neighbouring (regional) lymph nodes cannot be assessed Mx Presence of distant metastases cannot be assessed |

A final assessment of the TNM stage is only possible after tumour surgery.

Two further criteria are decisive for further treatment. Microscopic examination of the tumour tissue provides an indication of the malignancy of the tumour. This involves comparing the similarity of the cancer cells with the organ cells (see table below).

Cell similarity = grading according to UICC 2002

GX Specimen cannot be assessed histologically |

Secondly, it is of decisive importance whether the tumour could be completely removed (see table below).

R = Residual tumour (residual tumour after surgery)

RX Residual tumour cannot be determined |

Therapeutic options

The treatment methods depend on the stage of the tumour. The earlier a renal cell carcinoma is detected, the more favourable the prognosis for the patient. However, the patient's age and general state of health are also taken into account when choosing a therapy.

Curative surgery

Kidney removal (nephrectomy) with removal of lymph nodes

The standard therapy is the complete removal of the tumour-infected kidney. This provides a chance of a cure for renal cell carcinoma. The function of the removed kidney is then taken over by the remaining healthy kidney.

In some patients, it is possible to remove the kidney by laparoscopy (keyhole technique).

Partial kidney removal

The partial removal of smaller tumours is now an accepted procedure and promises the same survival rate as the complete removal of the kidney.

Tumour resection

Approximately 30% of all renal cell carcinoma patients already have lymph node or distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis. This is referred to as a palliative situation. There are indications that tumour removal in a palliative situation can bring a survival advantage if followed by systemic therapy. Tumour removal can therefore also be offered in the metastatic stage for patients who are not at significantly increased risk of surgery.

Systemic therapy

Targeted molecular therapies are the standard of care in the first and second-line treatment of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma; cytokine therapy only plays a subordinate role. At present, there are no clinically useful predictive biomarkers that can predict the response to one of these therapies. The specialist societies therefore recommend a risk-stratified approach based on the MSKCC risk score. Depending on the first- and second-line status as well as the risk profile, the substances sunitinib, pazopanib, axitinib, sorafenib, everolimus, temsirolimus, bevacizumab plus interferon-alfa and nivolumab were established for treatment in Germany in July 2016. The authorisation of cabozantinib in Germany is also imminent. The approval of a combination therapy of targeted substances is also expected for the first time: the combination of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor lenvatinib with the mTOR inhibitor everolimus. Although the combination of these two substances can extend the duration of remission, this comes at the cost of a significantly higher rate of side effects. The role that this combination therapy will play in the therapeutic landscape of renal cell carcinoma is therefore still the subject of scientific debate.

The optimal sequence of substances could only be determined by a research programme that explains the biological rationale for the respective sequence. In view of the advanced age of many patients with renal cell carcinoma, it is advisable to ensure patient compliance by paying attention to comorbidities and immediate pre-emptive treatment of side effects, thus achieving the maximum therapeutic benefit with a good quality of life in the given palliative treatment situation.